To round out the year, here are three tutorials on the blood gas machine, blood gas analysis and the blood gas printout.

The first tutorial looks at how oxygen is measured using the Clark Electrode on the blood gas analyser and demonstrates the importance of co-oximetry in modern blood analysis. From that the fractional saturation of hemoglobin with oxygen is derived.

The second tutorial explains the Glass Electrode that measures pH and PCO2. Subsequently I cover problems you might encounter with blood gas sampling. If you don’t want to watch the technical stuff, I strongly recommend you scroll to the middle of the tutorial (12 minutes in) as it covers information that all healthcare practitioners must know.

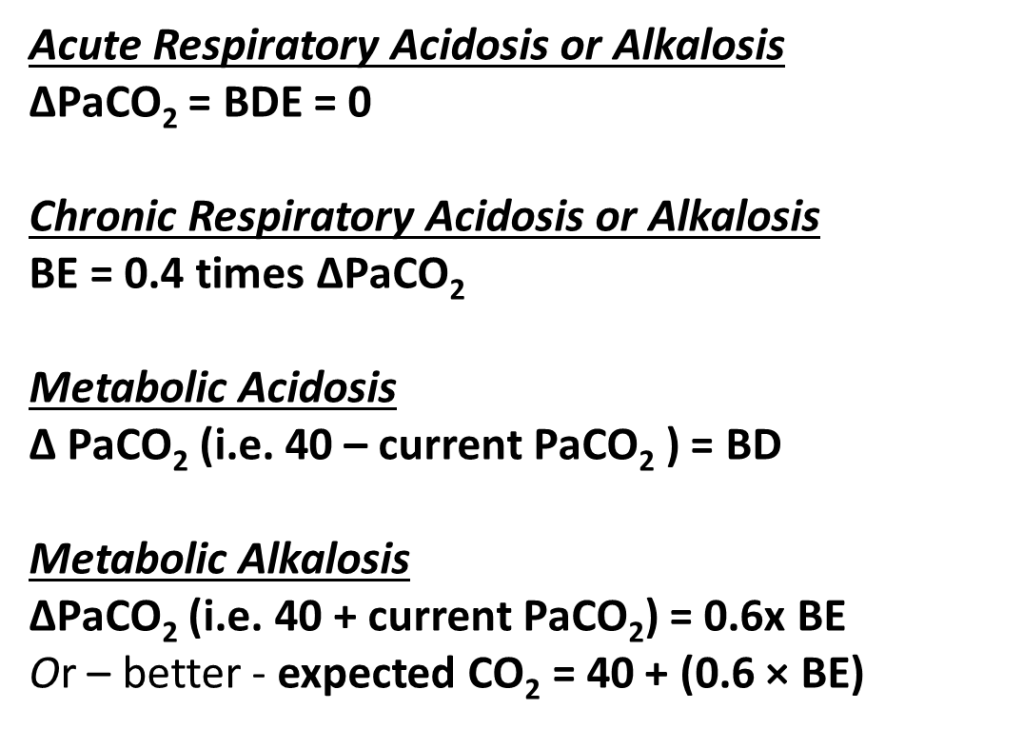

The final tutorial looks at all of that other data that appears on blood gas printouts that you may never have understood – and it can be really confusing – DERIVED or calculated variables (bicarbonate, temperature correction, TCO2, O2 content, Base Excess, Standard Bicarbonate, Anion Gap etc.). I cover both the Radiometer ABL machines and the GEM 5000. I guarantee you’ll learn something.